The roots of the ongoing conflict in eastern Congo extend far into the past, tracing back to an era when European colonial powers redrew the map of Africa to suit their own ambitions. To understand the present situation, one must first appreciate the deep and lasting impact of colonialism on the region. In the late 19th century, European states such as Belgium, Britain, and France embarked on a mission to exploit the vast resources of Africa. Their imperial ambitions were not merely about territorial expansion; they involved the systematic dismantling of indigenous systems of governance and culture. This colonial interference led to the imposition of artificial boundaries, the manipulation of ethnic identities, and the creation of institutions that primarily served the interests of the colonisers rather than the local populations.

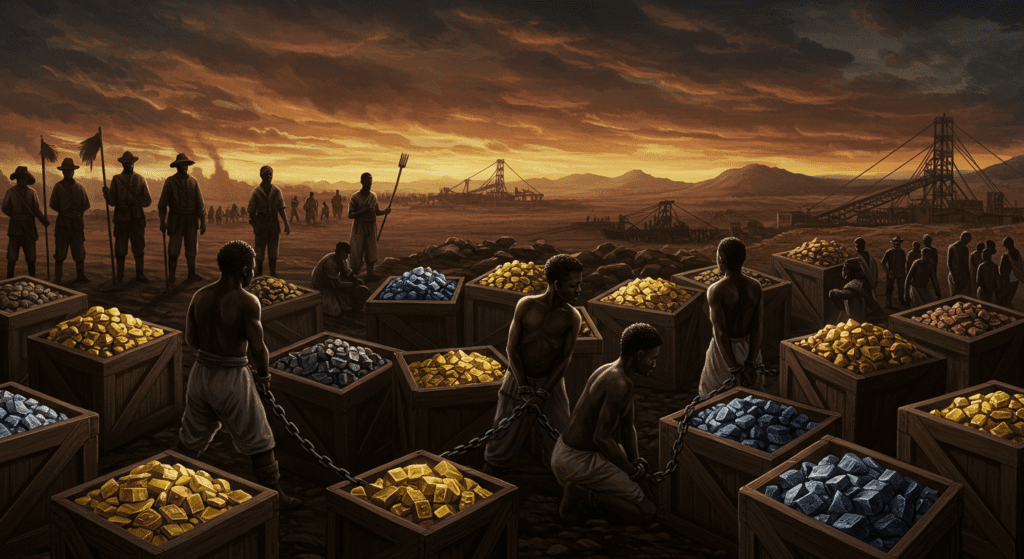

In what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the period of Belgian rule under King Leopold II was marked by extreme exploitation and brutality. Colonial administrators reorganised the social and economic fabric of the region to extract resources such as rubber, minerals, and timber. Traditional leadership structures were disrupted, and local communities were often forced into labour under harsh conditions. The policies of the colonial administration deliberately encouraged divisions among ethnic groups, as this made it easier to control the local populace. These early practices have left an indelible mark on the region, sowing seeds of division and mistrust that continue to influence contemporary politics.

The legacy of colonial rule is particularly evident in the way boundaries were drawn without regard for the intricate tapestry of local cultures and languages. These arbitrary borders have often split communities and grouped together peoples with little in common, thereby exacerbating tensions. As a result, the modern state of the DRC inherited not only the wealth of its natural resources but also a fractured social landscape that has struggled to achieve unity and effective governance.

A pivotal moment in the recent history of this region occurred after the 1994 Rwandan genocide. The mass slaughter of Tutsis in Rwanda forced hundreds of thousands of refugees to flee into eastern Congo, seeking safety from ethnic violence. This sudden influx of refugees, many of whom shared ethnic ties with the Tutsi community, intensified the existing tensions in the region. Rebel groups began to emerge, claiming that they were protecting the rights of Tutsis and other Congolese of Rwandan origin. One of the most well-known of these groups is the M23 rebel faction. While the rebels assert that their actions are in defence of ethnic minorities who have historically been marginalised, many observers argue that the conflict is also fuelled by economic interests.

The mineral wealth of eastern Congo is legendary. The region is rich in coltan, copper, cobalt, and gold—resources that are highly sought after in international markets. These minerals have become a significant source of revenue not only for rebel groups but also for multinational corporations and even neighbouring states. The profits generated from illicit mining and smuggling provide a steady stream of funds that help to sustain the conflict. In this sense, the war has become a complex web where historical grievances, ethnic identities, and economic motivations intersect. It is not simply a matter of local self-defence; the conflict has evolved into a battle for control over resources that are essential to global industries, such as technology and renewable energy.

External actors play a critical role in this equation. Rwanda, for example, has been frequently accused of providing support to rebel groups operating in eastern Congo. Although Rwandan officials claim that this support is aimed at protecting ethnic kin and addressing historical injustices, critics contend that such involvement is also a means of expanding political influence and securing access to the region’s lucrative resources. The dual nature of these claims—both humanitarian and strategic—illustrates how the colonial legacy continues to manifest in modern geopolitical manoeuvres.

Moreover, other regional players have found reasons to exploit the instability. Neighboring states and international companies often benefit from the ongoing conflict by capitalising on the chaos to secure favourable terms for resource extraction. The profits from mineral wealth, alongside the control of critical infrastructure, have attracted interest from countries looking to extend their influence over Central Africa. In this tangled web, the conflict is sustained not only by the internal divisions within the DRC but also by external interests that profit from the persistent instability.

Understanding the eastern Congo conflict requires recognising that the present is deeply intertwined with the past. The deliberate policies of European colonial powers—designed to divide and control—laid the groundwork for a legacy of instability that has proved remarkably enduring. The influx of Rwandan refugees following the genocide, combined with the colonial-era manipulation of ethnic identities, created conditions in which rebel groups could emerge and gain traction. These groups, while claiming to defend their communities, also exploit the region’s wealth, thus perpetuating a cycle of violence that benefits a select few while devastating countless lives.

The educational value of this narrative lies in its ability to demonstrate how historical forces shape contemporary conflicts. By tracing the origins of the conflict from the colonial era to the modern-day struggles, one can see how past injustices continue to have a tangible impact on current events. For instance, the exploitation of mineral resources in eastern Congo is not a new phenomenon—it is the continuation of a pattern that began with European colonisation. Similarly, the ethnic tensions that now fuel the rebellion can be traced back to deliberate strategies of division employed by colonial administrations. This historical perspective provides a clearer understanding of why the conflict persists and why various actors, both local and international, continue to benefit from the instability.

In conclusion, the conflict in eastern Congo is a multifaceted phenomenon rooted in a long history of colonial exploitation, ethnic division, and economic greed. It serves as a stark reminder that the effects of colonialism do not simply vanish with independence; they linger, influencing modern political dynamics and international relations. The ongoing war is sustained by a combination of local grievances and external interests that profit from chaos. To resolve this conflict, it is imperative to address the historical injustices that created these conditions in the first place, as well as to implement policies that ensure a more equitable distribution of resources. Understanding these deep-rooted causes is essential for anyone seeking to learn about the conflict, as it highlights the complex interplay of history, economics, and geopolitics in shaping the future of the region. Only through a comprehensive approach that acknowledges and rectifies the colonial legacy can lasting peace and stability be achieved in eastern Congo.

By examining this historical continuum—from colonial imposition and ethnic manipulation to modern economic exploitation—we gain a clearer picture of why the conflict endures and who benefits from its perpetuation. This lesson is invaluable for both scholars and the general public, illustrating that the past is never truly past, and that true progress requires a deep and honest reckoning with history.