In Ghana, the path to riches and renown doesn’t wind through hard work, ingenuity, or service—it barrels straight through the chaos of a coup. Emmanuel Kwasi Kotoka and Jerry John Rawlings stand as towering testaments to this twisted truth, their names etched into the nation’s psyche not for building but for breaking. Since 1969, Kotoka’s name has crowned Accra’s airport, a daily reminder of a man who stabbed Ghana’s first republic in the back. Rawlings, once a penniless flight lieutenant, vaulted from a failed 1979 coup to a legacy of power and wealth, his family now perched among the nation’s elite. These men didn’t earn fame through honor; they seized it through betrayal—and Ghana, still sleepwalking, keeps their statues polished while its true patriots fade into the dust.

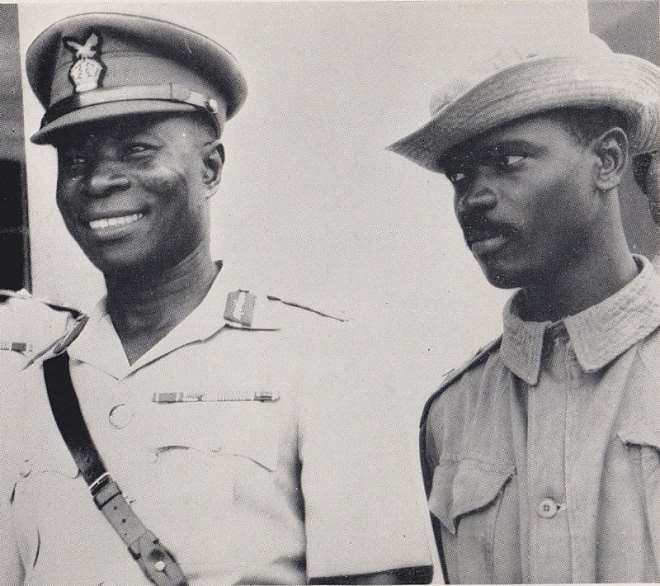

Kotoka’s story is a masterclass in disloyalty masquerading as liberation. In 1966, he spearheaded “Operation Cold Chop,” toppling Kwame Nkrumah—a visionary who, for all his flaws, laid the foundations of modern Ghana, including the very airport later named for his usurper. Kotoka didn’t just end a government; he derailed a dream, plunging Ghana into decades of instability that crippled its promise. His reward? A bullet in 1967 at the airport’s forecourt during a failed counter-coup—ironic, yes, but not enough to erase the bitter taste of his legacy. Two years later, in 1969, Prime Minister Kofi Busia’s government immortalized him with Kotoka International Airport, a decision dripping with the absurdity of honoring a traitor at a site Nkrumah’s vision birthed. Ghanaians pass through those gates daily, oblivious to the upside-down world they’ve accepted: a coup-plotter’s name soars while the architects of independence are footnotes.

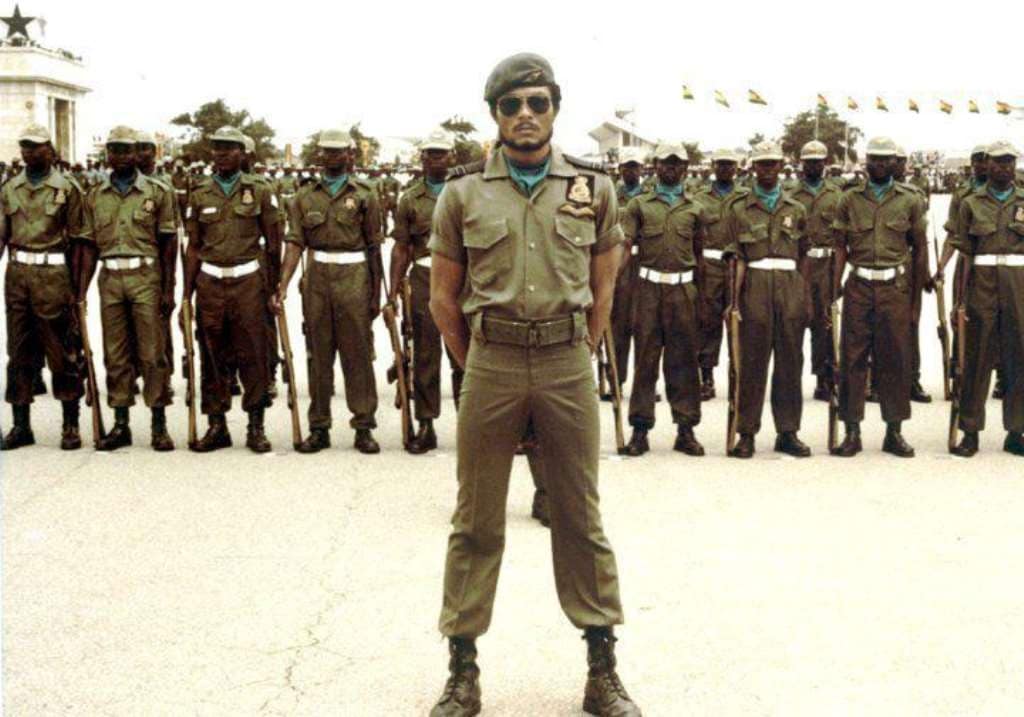

Then there’s Rawlings—dirt broke in 1979, as he himself admitted, when he first tried to storm the stage. His failed May coup landed him a death sentence, but fate flipped the script. Junior officers sprang him free, and by June, he’d ousted General Fred Akuffo, executing him and others in a bloody “housecleaning.” Two years later, in 1981, he struck again, toppling Hilla Limann’s elected government with promises of salvation. What followed was 19 years of rule—first as a junta strongman, then as a twice-elected president—marked by economic triage, populist swagger, and a trail of bodies. Today, the Rawlings family sits atop a fortune few can rival, a stark leap from the empty pockets of ’79. Coup number one failed, but the second built an empire. The lesson? In Ghana, a gun and guts outweigh a ballot or a plow every time.

This isn’t just history—it’s a diagnosis. Kotoka and Rawlings didn’t climb to fame and wealth by serving Ghana; they did it by shattering it. Kotoka’s coup gutted a fledgling republic, leaving scars that festered through decades of juntas and strife. Rawlings’ twin takeovers traded democracy for authoritarian theater, his “revolution” a veneer for personal ascent. Yet Ghana celebrates them—Kotoka with an airport, Rawlings with a mythic aura—while unsung heroes like J.B. Danquah, who bled for independence, or the countless farmers and teachers who built the nation’s spine, rot in obscurity. Why? Because Ghanaians slumber through a warped reality where betrayal is bravery, and chaos is charisma.

The airport naming isn’t just a quirk—it’s a symptom. Kotoka’s plaque mocks the memory of Nkrumah, whose Pan-African fire lit Africa’s path, and every plane that lands there hammers home the irony: a traitor’s monument on a patriot’s foundation. Rawlings, too, thrives in this delirium—lionized by some as a savior, his wealth and clout a quiet indictment of a system that rewards the barrel over the ballot. Meanwhile, Ghana’s honorable souls—those who didn’t shoot their way to the top—lie buried under neglect. The nation’s awake enough to mourn its woes but too drowsy to see the clowns it crowns.

It’s time to wake up. Tear Kotoka’s name off that airport and give it to a true titan—Nkrumah, or someone who didn’t build fame on Ghana’s broken back. Stop romanticizing Rawlings’ reign as redemption when it was a roulette of ruin and riches. Fame and wealth in Ghana shouldn’t be a coup’s spoils—they should be the fruit of honor, sweat, and sacrifice. Until Ghanaians demand that shift, they’ll keep living in this upside-down world, saluting traitors while the real heroes whisper from the shadows.