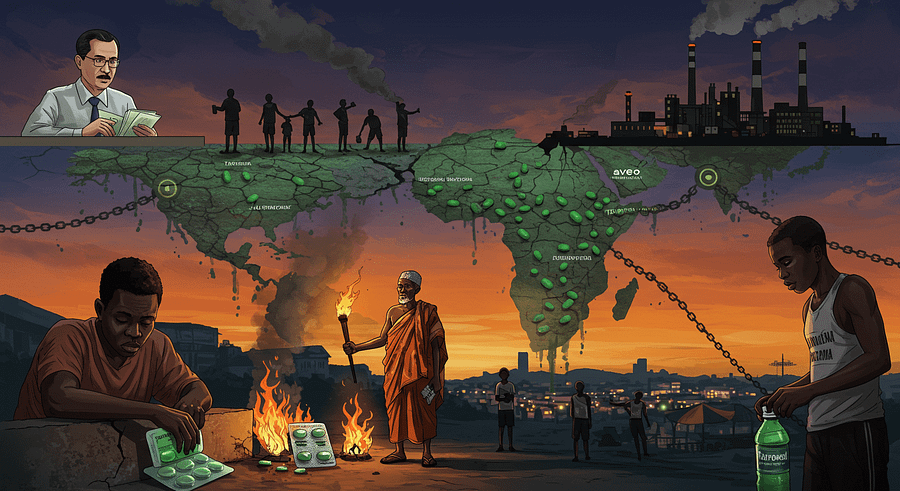

In the northern Ghanaian city of Tamale, a young man slumps against a wall, eyes barely open, clutching a green packet labeled “Tafrodol.” Hundreds of miles away, in Abidjan, Ivory Coast, a mother watches her teenage son stumble home, dazed from mixing the same drug with a cheap energy drink. These haunting images, captured by the BBC in February 2025, reveal a growing crisis sweeping West Africa—a flood of dangerous opioids traced back to Aveo Pharmaceuticals, a company in Mumbai, India. This isn’t just a public health problem; it’s a betrayal that echoes Ghana’s troubled past, from the foreign meddling of the 1966 coup to today’s exploitation of vulnerable lives. Ghana and Ivory Coast are fighting to hold on, but the damage is spreading fast.

The story begins with Aveo, exposed by the BBC’s “India’s Opioid Kings” investigation. This Mumbai firm produces pills like Tafrodol, combining tapentadol—a powerful opioid—and carisoprodol, a muscle relaxant so addictive it’s banned in Europe. No health authority anywhere approves this mix; it’s a risky, untested blend that can trigger seizures, stop breathing, or kill, especially when paired with alcohol—a common practice among young users. Despite this, Aveo has poured millions of these tablets into West Africa, slipping through loose borders and lax regulations. Undercover BBC reporters, posing as buyers, filmed Aveo’s director, Vinod Sharma, inside his factory. He showed off the drugs, admitting, “This is very harmful for their health,” before adding with a shrug, “but this is business.” Sharma outlined smuggling routes, bypassing Nigeria’s stricter ports for Ghana’s easier entry points: “I clear from India, you clear from your side.” Export records confirm it—millions of green packets from Aveo and its sister company, Westfin International, now litter streets from Tamale to Abidjan.

This trade breaks laws on both ends. India prohibits exporting unapproved drugs without permission, and Ghana and Ivory Coast have banned this deadly combo. Yet Aveo keeps shipping, turning desperation into profit—a betrayal that stings all the more for its familiarity. Ghana’s history offers a parallel: in 1966, the CIA quietly backed a coup that toppled Kwame Nkrumah, leaving a nation wary of outside hands. Now, India’s opioid flood adds a new chapter to that distrust, hitting communities already fragile from decades of upheaval.

In Tamale, the impact is heartbreakingly clear. Chief Alhassan Maham describes the drugs’ spread as “a blaze no water can quench.” He leads a team of 100 volunteers who raid dealers, seizing and burning piles of Tafrodol to protect their youth. “It steals their minds,” he told the BBC, his words heavy with loss. On Tamale’s streets, the toll unfolds daily—one young man, filmed in a stupor by the roadside, barely moved as flies buzzed around him. Others spoke of lives “lost” to addiction, trapped by a drug that Dr. Shukla, an expert cited by the BBC, says brings harsher withdrawal than tramadol, Ghana’s earlier opioid plague. Teens mix it with alcohol for a cheap high, not knowing each dose risks death. Ghana’s Drug Enforcement Agency joins the fight, torching seized stashes, but the battle feels endless. Ports like Tema, a known smuggling hub, leak despite crackdowns—corruption and gaps keep the supply flowing. This isn’t Ghana’s first rodeo; a 2018 tramadol surge led to action after a BBC exposé, but today’s wave, marked by Aveo’s green pills, hits harder.

Ivory Coast faces a quieter but equally devastating struggle. In Abidjan, a street vendor—let’s call him Kofi for his safety—shared, “Kids buy them cheap, mix them with energy drinks, and vanish into the night.” A mother there watched her son come home slurring, his future slipping away under the drug’s grip. Export logs show millions of Aveo’s tablets landing in Côte d’Ivoire, feeding a market built on its past as a drug transit point—heroin trails mapped in 2016 studies laid the groundwork. Now, those routes serve local users, fueled by poverty and open borders. Data is scarce, but Nigeria’s four million opioid users suggest a regional explosion, with Ivory Coast caught in the swell. The drugs’ wild potency—unregulated and untested—means every pill is a roll of the dice, a threat stealing youth in silence.

This crisis builds on a troubled past. The UN’s 2018 World Drug Report flagged tramadol’s rise in West Africa, but tapentadol-carisoprodol marks a darker turn—more lethal, less controlled. Economic hardship drives demand; jobless youth seek escape in cheap pills, and weak ports let them in. Beyond logistics, though, lies a deeper wound. Ghana’s 1966 coup, which killed 1,600 and sowed decades of chaos, left a lasting mark—a people taught to doubt power, a nation dazed by betrayal. Ivory Coast, too, carries scars from instability. Today’s drugs pile onto that pain, breaking families as addicts fade and draining hope from communities. Parents who survived coups passed caution to their kids; now, those kids face a new enemy, unhealed trauma meeting unchecked addiction.

Responses have come, but they’re playing catch-up. After the BBC’s sting, India’s Drugs Controller General, Dr. Rajeev Singh Raghuvanshi, banned the tapentadol-carisoprodol mix on February 21, 2025, raiding Aveo’s factory and seizing stock. India’s regulators promised tighter export rules but nodded to West Africa’s weak defenses—a fair point, yet it sidesteps their own failure to stop the flow earlier. Ghana burns what it catches, a fiery stand, while Ivory Coast’s efforts stay less visible, though regional voices grow louder. Nigeria’s drug chief, Brig. Gen. Mohammed Buba Marwa, calls it “devastating our youths, our families”—a cry that spans borders. Questions swirl around the WHO, too; the BBC suggested it certified Aveo, a claim unconfirmed but troubling if true, hinting at oversight failures akin to America’s opioid mess. Meanwhile, the pills already out there could harm for years, a lingering threat no raid can erase.

Still, there’s grit amid the gloom. Tamale’s volunteers and Abidjan’s quiet resilience show communities stepping up where systems falter. But grit alone won’t stem this tide—it needs more. Ghana and Ivory Coast face a flood through tainted gateways, their futures at stake. This isn’t just about health; it’s about reclaiming control from those who exploit weakness, from 1966’s shadows to Aveo’s greed. Sharma’s “business” excuse fuels anger—profits over people, a betrayal too familiar.

Wake up and fight: Ghana, Ivory Coast, and Africa must stand guard against this opioid invasion. Seal the ports, demand India answers for its lapse, and press the WHO for truth. Burning pills is a start, but building walls against the next wave matters more—communities like Tamale’s show how. These nations have endured coups, unrest, and now this; they deserve healing, not more loss. Stay super alert, because if history teaches anything, it’s that betrayal thrives when vigilance sleeps. The fight isn’t over—it’s just begun.